Results

- Data: RANZCOG Leadership

- Data: RANZCOG Affiliated Hospitals & Universities With an O&G Department

- Data: RANZCOG Survey

- Survey – Demographic Data

- Survey – O&G Leadership Data

- Table 5. ‘Do you currently hold a leadership positions within RANZCOG, University or your hospital?’

- Table 6. ‘Would you like to hold an additional leadership position now or in the future?’

- Table 7. ‘Would you like to hold an additional leadership position now or in the future?’

- Graph 1. ‘What factors stop you from seeking a leadership position or additional leadership positions?’

- Survey – O&G leadership thematic analysis

- Survey – Gender Bias Data

- Survey – Gender Bias Thematic Analysis

- Survey – Gender quota Data

- Survey – Gender quota thematic analysis

- Survey – Concluding thematic analysis

Contents

- Data: RANZCOG Leadership

- Data: RANZCOG Affiliated Hospitals & Universities With an O&G Department

- Data: RANZCOG Survey

- Survey – Demographic Data

- Survey – O&G Leadership Data

- Table 5. ‘Do you currently hold a leadership positions within RANZCOG, University or your hospital?’

- Table 6. ‘Would you like to hold an additional leadership position now or in the future?’

- Table 7. ‘Would you like to hold an additional leadership position now or in the future?’

- Graph 1. ‘What factors stop you from seeking a leadership position or additional leadership positions?’

- Survey – O&G leadership thematic analysis

- Survey – Gender Bias Data

- Survey – Gender Bias Thematic Analysis

- Survey – Gender quota Data

- Survey – Gender quota thematic analysis

- Survey – Concluding thematic analysis

Data: RANZCOG Leadership

In 2017 RANZCOG has a total female membership of 63% (1325 of 2530), a female specialist membership of 46% (945 of 2055), and a female trainee membership of 80% (380 of 475). This study’s results reveal that females remain in the gender minority in all national RANZCOG leadership roles (Table 1).

Educational leadership roles at RANZCOG (T&A state chair and ITP coordinators) most closely align with membership gender representation, where female specialists are overrepresented. The gender leadership gap is most pronounced at the highest level of leadership, the RANZCOG board.

Table 1. RANZCOG committees

| Committee Type | Number of Committee members | Female committee members |

|---|---|---|

| RANZCOG board* | 7 | 14% (1) |

| Members 10th RANZCOG Council* | 25 | 36% (9) |

| National Chairs* | 62 | 31% (19) |

| Training & Assessment State Chairs* | 7 | 71% (5) |

| (ITP) hospital Coordinators# | 32 | 53% (17) |

*National positions #ITP = Integrated Training Program

Data: RANZCOG Affiliated Hospitals & Universities With an O&G Department

The data from document review demonstrates that RANZCOG affiliated hospitals and university O&G departments demonstrate a gender leadership gap (Table 2 & 3). This gap closely aligns with the RANZCOG national committee statistics, with average female leadership being 26% for RANZCOG, 32% for RANZCOG affiliated hospitals, and 26% for university O&G departments in Australia and New Zealand.

Table 2. RANZCOG accredited hospitals Australia and New Zealand

| Country or State | Number of hospitals | Number of department heads | Females in department head position |

|---|---|---|---|

| NEW ZEALAND | 12 | 26 | 57.7% |

| NZ – North Island | 10 | 18 | 72.2% |

| NZ – South Island | 2 | 8 | 25% |

| AUSTRALIA | 86 | 256 | 22.7% |

| NSW | 25 | 55 | 27.3% |

| VIC | 22 | 64 | 37.5% |

| QLD | 16 | 30 | 26.7% |

| SA/NT | 9 | 25 | 16% |

| WA | 8 | 19 | 21% |

| ACT | 3 | 6 | 33.3% |

| TAS | 3 | 3 | 33.3% |

| TOTAL | 98 | 282 | 31.5% |

Table 3. Universities in Australia and New Zealand with O&G departments

| Country | Number of Universities | Number of department heads | Females in department head position |

|---|---|---|---|

| New Zealand | 2 | 3 | 66.6% |

| Australia | 18 | 20 | 20% |

| TOTAL | 20 | 23 | 26.1% |

There were two notable outliers in the data. First, the North Island of New Zealand is an outlier with an overrepresentation in leadership, both at the hospital and university level. Significantly contributing to this is Auckland City Hospital, the largest O&G department in New Zealand, staffed exclusively by females in leadership. Despite this variation in intercountry hospital and university female O&G leadership representation, both countries had matched membership levels of desire for future/additional leadership, and matched levels of leadership barriers. Second, within Australia, Westmead hospital was a notable as an outlier with 80% female leadership. In contrast, amongst tertiary hospitals, Royal Prince Alfred Camperdown, Women’s and Children Adelaide, and the Gold Coast University hospital, had no females in leadership.

Data: RANZCOG Survey

An online membership wide survey (Appendix 1) was disseminated via email on August 15th 2017, running for 21 days total, with a reminder email on day 14. A total of 770 responses were received (30.4% of members: 27.3% of male members, 33.1% of female members), with a 93% full completion rate.

Survey – Demographic Data

Survey responder demographics (Table 4) are statistically representative of RANZCOG membership trainee and specialist mix (p=0.32). The responder sample is however not perfectly representative of RANZCOG membership gender, with a statistically significant greater proportion of female responders than RANZCOG female members (p=0.0079). This is also true for the specialist cohort, with a statistically significant greater number of specialist female responders than RANZCOG specialist female members (p=0.047). The responder sample of trainee gender is representative of the current RANZCOG trainee gender (p=0.319).

Table 4. Demographic findings from Survey respondents

| What is your gender? (n=770) | n | % | 2017 membership | 2017 specialist | 2017 trainee |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Male | 329 | 42.7% | 47.6% (1205) | 54% (1110) | 20% (95) |

| Total Female | 439 | 56.9% | 52.4% (1325) | 46% (945) | 80% (380) |

| Other | 3 | 0.4% | *N/A | N/A | N/A |

| What is your membership status? (n=770) | |||||

| Trainee | 134 | 17.4% | 18.7% (475) | ||

| Fellow | 637 | 82.6% | 81.2% (2055) | ||

| Age category (n=770) | |||||

| 20-29 | 23 | 3% | |||

| 30-39 | 185 | 24% | |||

| 40-49 | 208 | 27% | |||

| 50-59 | 195 | 25.3% | |||

| 60-69 | 118 | 15.3% | |||

| 70+ | 42 | 5.6% | |||

| Country of primary practice (n=770) | |||||

| Australia | 638 | 82.8% | 88.4% (2237) | 86.3% (1773) | 98% (464) |

| New Zealand | 124 | 16.1% | 11.6% (293) | 13.7% (282) | 2% (11) |

| Other | 6 | 0.8% | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Not practicing | 3 | 0.4% | 0 | 0 | 0 |

*N/A = Data not available from RANZCOG as not collected prior to July 2017.

Survey – O&G Leadership Data

95% of survey responders answered questions pertaining to leadership (Appendix 1, q5 & q6), with 31% of respondents holding a current RANZCOG, University or hospital leadership position.

Male responders were statistical significantly more likely to hold current leadership roles than female responders (Table 5). This held true for male specialist, but not male trainee members. Both male and female specialist members were more likely to hold leadership positions than both male and female trainee members. With regards to leadership aspirations, female responders were more likely to desire additional or future leadership positions than male responders (Table 6). Irrespective of site (RANZCOG, University or hospital), female specialists were statistically more likely to desire additional or future leadership positions (Table 7). This is significant, as responders in ‘outlier’ contexts that contained high levels of female leadership, expressed similar levels of desire than their colleagues in contexts with little or no female leadership. There was no difference observed between male and female trainees with regards to leadership position desire (p = 0.279).

Table 5. ‘Do you currently hold a leadership positions within RANZCOG, University or your hospital?’

| All | Fellows | Trainees | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| Male | 39.35% (122) | 60.65% (188) | 41.52% (120) | 58.48% (169) | 9.52% (2) | 90.48% (19) |

| Female | 24.76% (104) | 75.24% (316) | 30.03% (94) | 69.97% (219) | 9.35% (10) | 90.65% (97) |

| ALL | 32.05% (226) | 67.95% (504) | 35.77% (214) | 64.23% (388) | 9.44% (12) | 90.56% (116) |

| p-value | < 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.979 |

Table 6. ‘Would you like to hold an additional leadership position now or in the future?’

| All | RANZCOG | Within my hospital | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| Male | 46.78% (145) | 53.22% (165) | 28.39% (88) | 71.61% (222) | 9.52% (106) | 90.48% (204) |

| Female | 62.38% (262) | 37.62% (158) | 40.24% (169) | 59.76% (251) | 9.35% (200) | 90.65% (220) |

| ALL | 53.58% (407) | 45.42% (323) | 34.32% (257) | 65.68% (473) | 9.44% (306) | 90.56% (116) |

| p-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

Table 7. ‘Would you like to hold an additional leadership position now or in the future?’

| All | Specialist | Trainees | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| Male | 46.78% (145) | 53.22% (165) | 43.94% (127) | 56.06% (162) | 85.71% (18) | 14.29% (3) |

| Female | 62.38% (262) | 37.62% (158) | 58.15% (182) | 41.85% (131) | 74.77% (80) | 25.23% (27) |

| ALL | 53.58% (407) | 45.42% (323) | 51.05% (309) | 48.95% (293) | 80.24% (98) | 19.76% (30) |

| p-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.279 |

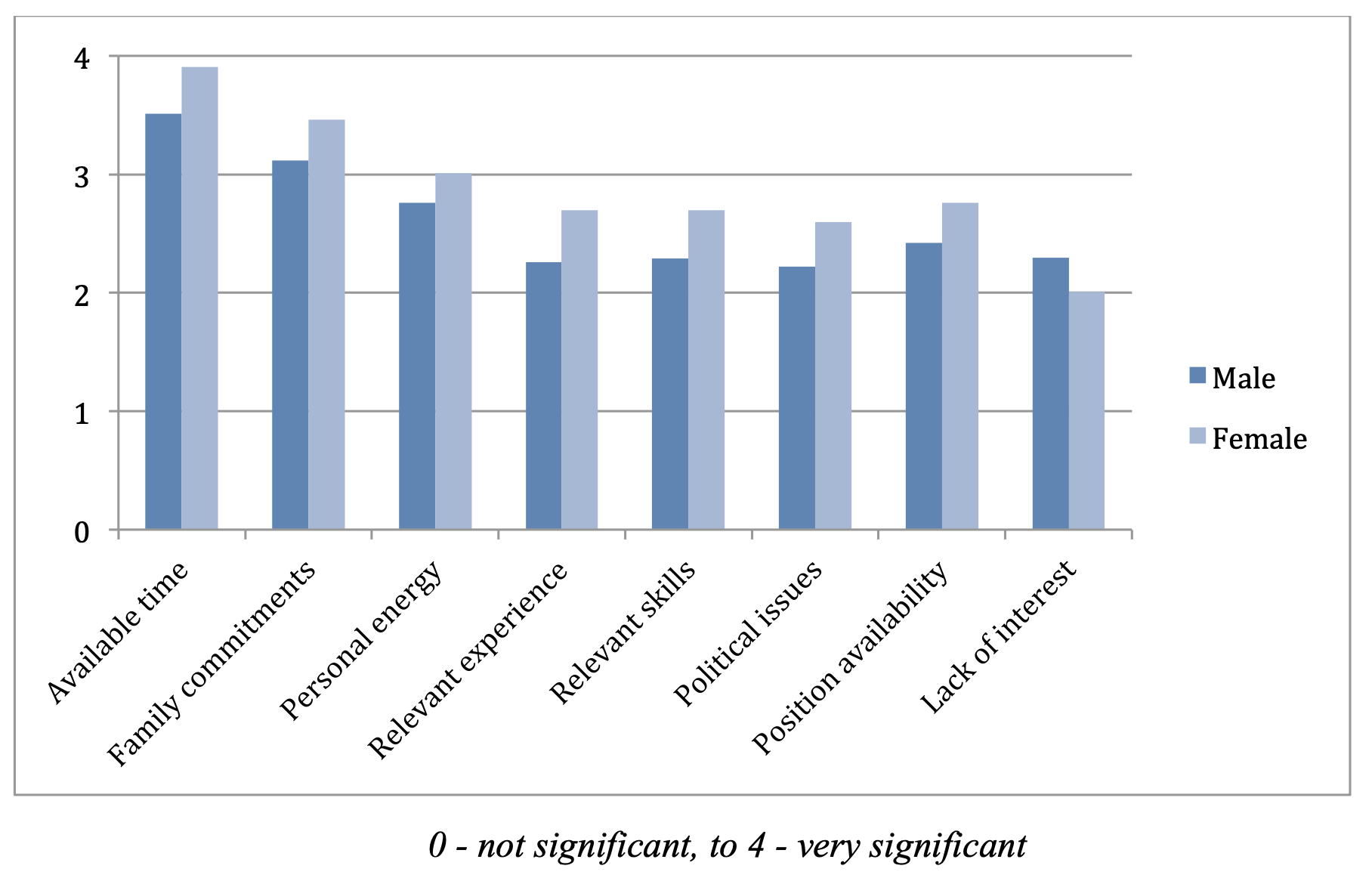

The top four identifiable barriers (available time, family commitments, personal energy and position availability) to future leadership were consistent between genders (Graph 1). Women rated all identifiable barriers higher on average than their male counterparts, except for ‘lack of interest’.

Graph 1. ‘What factors stop you from seeking a leadership position or additional leadership positions?’

Survey – O&G leadership thematic analysis

Twenty percent of responders who completed the quantitative survey responses on O&G leadership also provided free text comments to the question ‘any comments regarding O&G leadership?’ Of the 146 members with free text responses, 51% were female and 49% male. Among the trainee sample only female trainees responded (<1% of overall responders).

As described in the methodology, Braun and Clark’s thematic analysis framework (187) was used to facilitate identification of themes. Aiming for a snapshot of information, and some perspectives on aspirations and views about leadership, ‘leadership barriers’ emerged as the strongest theme in this section of responses.

Trainee responders

Among the female trainee responder cohort (n=14) the majority reported desiring leadership (62.4%), with more than 85% reporting an awareness of gender barriers to future leadership opportunities. Very few leadership positions are available for trainees. In keeping with this, only one trainee identified as currently holding a leadership positions. This was within RANZCOG as a trainee representative for the college council, an important place for trainees to voice their concerns or support for curriculum changes.

Female specialist responders

In response to the question ‘any comments regarding O&G leadership?’, the overwhelming singular theme from textual analysis amongst female specialists was that of ‘leadership barriers’. This was found in 83% of female responder comments. Within this theme of ‘leadership barriers’, subthemes of ‘disillusionment’ (40% of responses), ‘financial and time’ barriers (27% of responses), and ‘gender barriers’ (22% of responses), and ‘learning leadership’ (13% of responses), were present.

Disillusionment

Comments demonstrating a ‘disillusionment’ theme most commonly pertained to members’ disillusionment with the ‘institution’ of RANZCOG (46% of comments). These are found in Box 2. Acknowledging the enormous diversity that will exist within the RANZCOG membership, these comments reveal that these RANZCOG members do not feel authentically represented by their leadership. Other comments relating to disillusionment referred to hospitals or health systems cultures (Box 3).

| Box 2 |

|---|

| “college is very conservative and dominated by private male practitioners that are not representative of the trainees or fellows” (F, 50+, Australia) |

| “nothing more than an organised union of thugs who are there to protect the private sector mates club. Comparison with RCOG and in recent times ACOG are disgraceful and embarrassing” (F, 50+, Australia) |

| “serious concerns about the structure and viability of the current college staff environment. No confidence in current CEO” (F, 60+, Australia) |

| “RANZCOG leadership seems most interested in their own views and their colleagues pockets, not what is best for women. Also no respect for views of members” (F, 50+, Australia) |

| “it is very tightly controlled by a few who actively make sure that other potential leaders are not allowed to get a toe hold” (F, 50+, Australia) |

| Box 3 |

|---|

| “I have previously held leadership positions. The experience was frustrating with most responsibility and accountability with very little power to influence change” (F, 50+, New Zealand) |

| “thankless to be in leadership in the DHBs in NZ and no real opportunity to effect change” (F, 40+, New Zealand) |

| “I have had enough of being a leader. For clinicians to pursue leadership, they need supportive administration, otherwise it is hell” (F, 60+, Australia) |

| “health systems are increasingly out of the control of medical people, and leadership often feels futile and personally damaging” (F, 30+, Australia) |

Time and Financial Barriers

Responders indicated available ‘time and financial’ considerations were strong barriers to leadership (graph 1). This was further reflected in responder free text comments (Box 4). Among this responder cohort, comments on time as a barrier were more prevalent than financial barriers. This was particularly so amongst the under 50-year-old responders, and possibly reflects increased parenting demands within this age cohort. Within this subtheme responders explicitly referenced the impact of leadership on family time.

| Box 4 |

|---|

| “a very large time commitment is involved in RANZCOG leadership, which incurs opportunity cost (lost income from paid work) or impacts on family time” (F, 40+, Australia) |

| “public health units are very inflexible regarding family time” (F, 40+, Australia) “time and administrative support is often lacking” (F, 50+, New Zealand) |

| “time consuming and not renumerated” (F, 50+, Australia) |

| “it is difficult fitting all things in” (F, 40+, Australia) |

| “very time consuming, bigger commitment than most people willing to make” (F, 60+, New Zealand). |

Gender Barriers

Many of the comments related to gender barriers revealed the common thread of ‘denial of opportunity due to gender’ (Box 5). Whether real or perceived, these comments suggests multiple issues including a system failure with the feedback process if unsuccessful applicants feel they are only left with ‘gender’ as a discriminator for promotion. It also strongly suggests the process of selection needs improved transparency to ensure gender is not a real or perceived discriminator.

| Box 5 |

|---|

| “men of same age and ability promoted ahead of women in hospital setting” (F, 50+, Australia) |

| “mostly male dominated and controlled. Males still have the majority of decision-making regarding appointments within hospitals and college. Often certain women that are chosen for a leadership role are those that are non-threatening and unlikely to advocate on behalf of rest” (F, 30+, Australia) |

| “I have been denied leadership roles because of the male dominated atmosphere” (F, 60+, Australia) |

| “talent in young women is overlooked and undervalued” (F, 30+, Australia) |

| “male dominated and can still be difficult to break through the glass ceiling even when you are clearly the best (wo)man for the job” (F, 40+, Australia) |

Learning Leadership

A further theme that arose within this responder cohort was that of training for, or ‘learning leadership’ (Box 6). These comments were strongly directed toward registrar training years, especially the early years of the formal training program, and were most prevalent amongst a younger age cohort (> 30 years). Interestingly, despite the dominant female leadership of New Zealand (Table 2 and 3), female responders from New Zealand equally commented on their desire to ‘learn leadership’.

| Box 6 |

|---|

| “lack of leadership training is an issue” (F, 30+, Australia) |

| “not enough training throughout the training years” (F, 30+, New Zealand) |

| “minimal training opportunities for development of this during early training years” (F, 30+, New Zealand) |

| “would appreciate more leadership training within O&G and opportunities to attend leadership workshops” (F, 30+, Australia) |

| “it would be good if the college supported trainees and fellows in the early years of leadership” (F, 40+, Australia) |

| “I wish we had training on leadership during ITP etc training” (F, 30+, New Zealand) |

Male specialist responders

Male responders contributed to 48.6% of the free text comments. The ‘barriers to leadership’ theme again predominated (60% of responders), and was followed by responders noting their past or current leadership role (31% of responders) as their only response. This is consistent with RANZCOG’s historically masculinised leadership.

Within this theme ‘barriers to leadership’, the subthemes of ‘disillusionment’ (60%) ,‘financial and time barriers’ (22% of responses), ‘learning leadership’ (19%), and ‘a changing of the guard’ (16%) predominated. Among male responders there were no comments relating to ‘gender bias’ as a barrier to leadership. This was consistent with the lower self-reported prevalence of gender bias in the male specialist cohort (Table 8).

Disillusionment

Comments pertaining to the ‘disillusionment’ theme were most commonly focused towards the culture within the current leadership (68% of responses – Box 7), towards with RANZCOG itself (23% of responses – Box 8), and to administrative challenges (9%). Comments here suggested a strong sense of disenchantment and pessimism with past and/or current leadership position. Although present in the female specialist cohort, these were much more commonly seen amongst male respondents.

| Box 7 |

|---|

| “could get backstabbed” (M, 50+, Australia) |

| “difficult when you are surrounded by megalomaniac bastards” (M, 60+, Australia) |

| “our profession has a dearth of effective authentic leadership at every level” (M, 30+, Australia) “too many people want to grandstand” (M, 50+, Australia) |

| “quality of current leadership is underwhelming” (M, 70+, Australia) |

| “medical politics is even dirtier than state/federal politics” (M, 60+, Australia) |

| Box 8 |

|---|

| “RANZCOG leadership has shown a lack of courage” (M, 50+, Australia) |

| “RANZCOG has elections that have a set pattern of ascendancy in a rigid old boys network that prevents other from outside joining and progressing through the ranks” (M, 40+, Australia) |

Time and financial barriers

Within this cohorts’ free text comments ‘time and financial barriers’ was another common subtheme (Box 9). This correlated with responses seen from male responders in graph 1. Within this subtheme male responders made more comments on ‘financial barriers’ than with female responders. This may indicate a higher level of financial responsibility among the male responders, and/or the type of practice these responders work within (as public practice more commonly makes financial allowances for leadership activities).

| Box 9 |

|---|

| “under paid and under appreciated” (M, 60+, Australia) |

| “time constraints the most important barrier” (M, 60+, Overseas) |

| “leadership roles require time commitments that a busy clinician has great difficult with from all aspects, family, income, life balance” (M, 60+, Australia) |

| “remuneration discrepancies with the private sector keep many a good leader out of leadership roles” (M, 50+, Australia) |

| “I will only do it when I have time to do it properly” (M, 30+, New Zealand) |

Learning Leadership

As seen with female responders, the theme of ‘learning leadership’ arose from male responders. These comments were strongly associated with the need to be taught leadership, and promote mentorship (Box 10). Interesting this cohort of responders was an older cohort compared to female responders raising these issues.

| Box 10 |

|---|

| “we should have a module of training dedicated to clinical leadership, how to run a department, safety and quality, and mentoring. We should be better at teaching this stuff!” (M, 60+, Australia) |

| “I have not recognised the college as being a resource for developing the necessary skills to be an effective leader” (M, 50+, Australia) |

| “there is no training” (M, 50+, Australia) |

| “younger colleagues should be actively mentored” (M, 60+, Australia) |

Changing of the guard

A new subtheme arose from male responder free text comments that was not seen previously. This theme implied a ‘changing of the guard’, with responders looking to pass on their leadership knowledge and/or positions to the next generation, or to encourage a higher turnover through RANZCOG leadership positions (Box 11). Responders among this theme report a higher rate of past and current leadership roles. A minority of responders countered the ‘changing of the guard’ theme, commenting, “they should listen more to their tribal elders” (M, 70+, Australia), and “we have entered a new era of ageism” (M, 70+, Australia). These were from respondents all over the age of 70 years, and possibly reflect perceived judgement of their leadership capacity reducing with age.

| Box 11 |

|---|

| “needs younger input, with less academic representation” (M, 70+, Australia) |

| “have previously had college leadership role – younger fellows now better suited” (M, 60+, New Zealand) |

| “been there, done that, time for younger ones” (M, 60+, Australia) |

| “younger colleagues should be actively encouraged and mentored as involvement is rewarding” (M, 60+, Australia) |

| “too many old males running the show as far as college goes. Need shorted terms, faster turnover, less redundant long serving members” (M, 40+, Australia) |

Survey – Gender Bias Data

Question 9 of the survey (Appendix 1) asked responders ‘have you experienced gender bias during your training or specialist years?’, with just under half of all responders reporting gender bias (Table 8). Female responders were more likely to report gender bias than male responders. Among specialists, females were more likely to report gender bias than males. Within the trainee cohort, a trend toward higher levels of gender bias amongst female was present, but did not reach statistical significance. When analysed as separate cohorts, trainees were also more likely to report gender bias than their specialist colleagues (p=0.0057).

Table 8. ‘Have you experienced gender bias during your training or specialist years?’

| All | Specialists | Trainees | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| Male | 28.76% (88) | 71.24% (218) | 27.71% (79) | 72.28% (206) | 42.86% (9) | 57.14% (12) |

| Female | 54.01% (222) | 45.99% (189) | 53.07% (164) | 46.93(145) | 56.86% (58) | 43.14(44) |

| ALL | 41.38% (310) | 58.62(407) | 40.39% (243) | 59.61(351) | 49.86% (67) | 50.14% (56) |

| p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.241 |

* Combined ‘No’ and ‘Unsure’, so comparing men to women answering ‘Yes’ versus ‘Not Yes’.

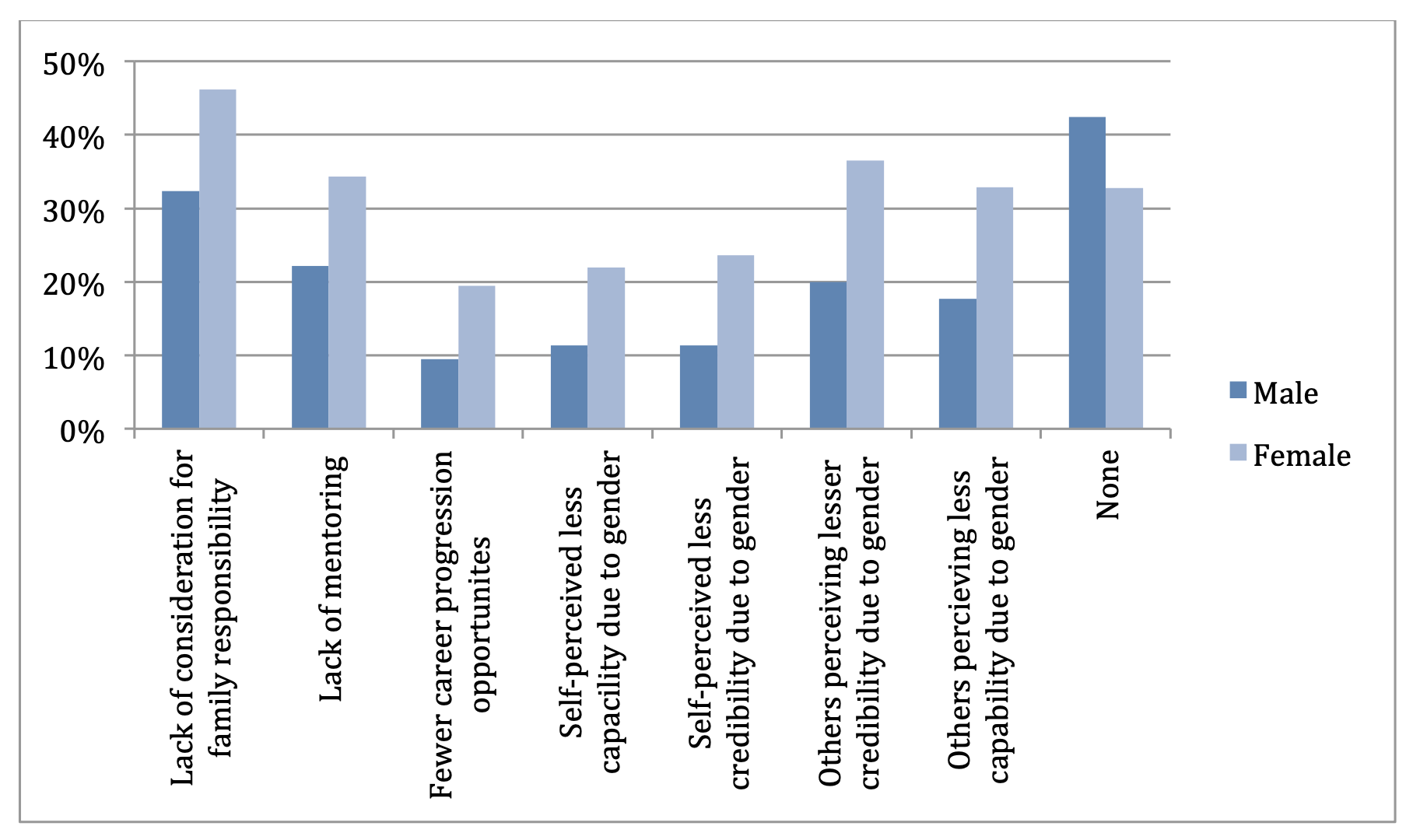

Question 10 of the survey (appendix) was a closed question pertaining to gender biases that limit leadership, with eight listed answer options. In response to this question, ‘what gender biases, if any, do you believe exist for trainees and specialists that limit leadership opportunities?’, responders identified ‘lack of consideration for family responsibilities’, ‘others perceiving a lesser credibility due to gender’, ‘lack of mentoring’ and ‘others perceiving a lesser capability due to gender’, as the leading four biases (graph 2). There were however significant differences across female and male responders. Female responders listed ‘lack of consideration of family responsibility’ (46%) as their most prevalent gender bias. This remained true for both female trainees and female specialists. In contrast, male responders listed ‘none’ as the most common (43%) gender bias that limit leadership opportunities. Within the male trainees cohort family responsibilities (33%) was the most common gender biases. Of interest mentoring ranked as a third most prevalent gender biases for female trainees, but did not reach the top five for male trainees, suggesting improved mentoring opportunities for males trainees.

Graph 2. ‘What gender biases, if any, do you believe exist for trainees and specialists that limit leadership opportunities?’

Survey – Gender Bias Thematic Analysis

Twenty percent (20%) of survey responders provided free text responses to the question ‘any comments regarding O&G gender bias?’. Using the same inductive thematic analysis (187) approach described above, coded themes from the data set were identified.

Trainee responders

Trainee responses represented less than 1% of the free text comments. All three male responder comments reflected awareness that both males and females could experience gender bias. One example of this was “have observed in different departments biases towards both genders“ (M, 30+, Australia).

The 17 female trainees responding with free text comments held subthemes reflecting the statements: ‘female gender bias is present’ (12/17), ‘we risk male gender bias’ (3/17) and ‘gender bias does not exist’ (2/17). Although the majority of respondents acknowledged gender bias could exist for both males and females, comments strongly weighted toward female gender bias (Box 12). Two responders noted experiencing gender bias from other females, with an example from one responder: “women need to be aware that they themselves hold gender bias against other women. Women hinder other women from leadership” (F, trainee, 30+, Australia).

| Box 12 |

|---|

| “despite being in a predominantly female department, there is very much a bias” (F, 40+, New Zealand) |

| “some gender bias is intrinsic to working as a doctor in a field that was previously male dominated. Patients sometimes see young women as nurses/midwives, with male medical students perceived to be higher role in the clinical team” (F, 20+, Australia) |

| “I have had assumptions made about the direction I intend my career to go based on my gender” (F, 30+, Australia) |

Female specialist responders

Female specialist responses contributed to 50% of free text comments. The prevailing theme for this cohort was that of ‘female gender bias is present’ (57%). Fourteen percent (14%) of responders indicated they did not believe gender bias existed either in their own institutional setting or in the broader speciality. Other comments included those noting ‘gender bias is improving’ (11%), ‘we risk male gender bias’ (8%), and ‘males are now under-represented’ (5%). No comments refuted the presence of gender bias.

Female gender bias is present

Several data extracts involving the theme ‘female gender bias is present’ were made. Some described personal stories, one alluded to the pipeline’, while others acknowledged the gender biased culture around them (Box 13).

| Box 13 |

|---|

| “I know several females who were overlooked for head of unit positions that were given to less qualified males. It is still happening”(F,40+, Australia) |

| “I recognise it more and more as I get older”(F, 50+, Australia) |

| “I am so dismayed and depressed by what I see around me that I am planning to leave the profession as soon as possible” (F, 50+, Australia) |

| “there are lesser credentialed men getting positions of leadership and career pathways mapped out for them on the basis of nepotism old school networks and gender bias all the time”(F, 40+, Australia) |

| “6 board members, one woman. How many council members are women? Not many. Speaks for itself really”(F, 50+, Australia) |

| “men in positions of power see younger men as natural successors. CREI committee 100% male” (F, 30+, Australia) |

| “it is very persistent despite the larger number of women in the profession”(F, 30+, Australia) |

Within this theme of ‘female gender bias is present’, subthemes of ‘lesser capable surgically’ (Box 14) and ‘pregnancy and parenting’ dominated (Box 15).

| Box 14 |

|---|

| ‘females not considered real surgeons, unable to balance fertility, training and professional lives, ‘only busy coz they are females ‘… every. Single. Day. So over it” (F, 50+, Australia) |

| and “didn’t’ find this to be an issue until I started being seriously interested in complex gynae surgery. Then came across perceptions about how I would not be as good after I had kids” (F, 30+, New Zealand) |

| Box 15 |

|---|

| “I have received significant gender bias - verbally stated that didn’t want female trainees as they were difficult personalities to work with and took too much time off for family purposes” (F, 40+, Australia) |

| “I have experienced direct bias during training due to pregnancy – not offered training role even though I was the most experienced registrar, on the basis on pregnancy alone” (F, 50+, Australia) |

As noted amongst the female trainee responders, the following statement provided an insightful recognition that females too can all hold female gender biases: “bias even from female training supervisor – got away with comments about female registrar than a male supervisor would have dared passed judgement on” (F, specialist, 40+, New Zealand). Recognising our own implicit biases is an invaluable step towards challenging all biases (42). Interesting these comments came from both Australian and New Zealand responders, with the later location the outlier for higher levels of female representation in leadership.

Male specialist responders

Male specialists provided 38% of the free text comments to the question ‘any comments regarding O&G gender bias?’. The majority (48%) of comments pertained to the theme ‘male gender bias is present’ (see below). Eighteen percent (18%) of responders indicated gender bias no longer existed, or was never present, in O&G. Examples of this are included in Box 16. Counter to this cohort were the 17% of male specialist comments that pertained to the presence of female gender bias (Box 17).

| Box 16 |

|---|

| “I have not personally seen any gender bias in the field of O&G” (M, 60+, Australia) |

| “these biases no longer exist in the hospitals and university within which I work” (M, 50+, Australia) |

| Box 17 |

|---|

| “I know of female trainees concerned about having a pregnancy and how it will affect this years job and hence getting a job for next year” (M, 50+, Australia) |

| “training institutions and some directors still hold that women are not as good as males, despite the current numbers of female trainees” (M, 70+, Australia) |

Male gender bias is present

The overwhelming singular theme in response to ‘any comments regarding gender bias’ was that of ‘male gender bias is present’ (Box 18). This was present in 48% of free text comments from male specialist responders. Within this theme existed a subtheme of ‘patient preference for female providers’ (Box 19). Within the public system, consumer choice is balanced, often at odds, with the training needs of males within the profession.

| Box 18 |

|---|

| “have witness female trainees getting more training and attention from male supervisors than myself” (M, 50+, New Zealand) |

| “it’s a real thing’. Men are treated as second class citizens” (M, 50+, Australia) |

| “with less men in the workforce I see more bias to men than the opposite traditional gender bias of previous years” (M, 60+, |

| “if bias existed before it has now swung the other way and possibly too far” (M, 50+, Australia) |

| Box 19 |

|---|

| “marked gender bias with patients preferring female clinicians”(M, 30+, Australia) |

| “it is clearly a major issue for young male trainees and young male consultants” (M, 50+, Australia) |

| “as a male, many patients choose not to or complain about seeing me”(M, 40+, Australia) |

| “male medical students interested in obstetrics often miss out on procedures and bed side examination because of their gender” (M, 70+, Australia) |

Survey – Gender quota Data

Questions 12 and 13 asked responders about quota use within RANZCOG with the following questions, ‘should RANZCOG consider a gender quota system for federal council and state councils?’. The majority of responders opposed quota use for federal and state council (63% and 65% respectively, Table 9). This remained true among specialist (66%) and trainee responders (50%). Between genders, female responders were statistically significantly more likely to support gender quotas, compared to their male colleagues, at both federal and state level.

Table 9. Gender quotas

| Federal council | State council | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Unsure | Yes | |

| Male | 13.1%(40) | 77.4%(236) | 9.5%(29) | 12.46%(38) |

| Female | 29.02%(119) | 52.44%(215) | 18.54%(76) | 28.54%(117) |

| ALL | 22.24%(159) | 63.08%(451) | 14.68%(105) | 20.5%(155) |

| p-value | <0.001* | <0.001* |

*’No’ and ‘Unsure’ were combined to indicate ‘Not Yes’ in the statistical analysis. Statistical significance remained when comparing ‘Yes’ and ‘No’ and ‘Yes’ and ‘Not Yes’

Survey – Gender quota thematic analysis

Among the 93% of responders who answered questions on gender quotas (q 14, Appendix 1), 33% provided written comments to the question ‘any comments regarding gender quotas?‘. This question attracted the highest number of free text responses from the survey. Within these responses 63% of respondents articulated their opposition to gender quota use, similar to the 63% and 65% that opposed federal and state council quotas seen in table 9.

Male trainee responders

Six of the 21 male trainees (29%) provided written comments on gender quota. Here an equal proportion of responders supported (3/6) and rejected (3/6) the proposal of quota use. Trainees opposed to quotas expressed statements including merit including ‘use the most capable, qualified and motivated person for the job no matter what gender’ (M, 40+, New Zealand) . Those trainees in favour of quotas expressed statements including ‘I believe gender quotas, in general, are a good idea. Both, so that the representation is more representative, and because I believe better gender balance makes for better leadership’ (M, 30+, Australia).

Female trainee responders

Of the total 111 female trainees, 23 (21%) provided free text comments on gender quota use. Seventy eight percent (78%) of responses indicated an opposition to gender quota use, with ‘merit first’ as the sentiment expressed by over 95% in this cohort. Comments reflecting this included; “should be talent, interest and ability based alone” (F, 30+, Australia), and “it should be person who’s best for the job” (F, 20+, New Zealand). It is worth acknowledging one outlying comment; ‘gender quotas are unfair to people with potential, but do not belong to a specific gender’ (F, 30+, Australia). This comment challenges traditional binary gender identities, risking discrimination against those who identify as neither male nor female.

Free text comments from female trainee responders who supported gender quotas included; “minimum quotas should be introduced for both genders. Currently there are fewer female specialists holding leadership roles with RANZCOG. As the number of female specialists increase, there will be under-representation of male specialists” (F, 30+, Australia). This potential impact on male representation within RANZCOG leadership was also expressed by three of the responders who opposed gender quotas.

Male specialist responders

Male specialists represented 44% of the responders commenting on gender quota use, with seventy eight percent (78%) of responders indicating they did not support gender quotas. The statement ‘best person for the job’ reflected the dominant theme, with ‘merit’ (51%) and ‘the pipeline’ (26%) the subtheme present within this responder cohort. Other comments remarked on the importance of ‘equality for all’ and consideration for a ‘gender quota’ minimum.

Best person for the job

Within the theme ‘best person for the job’, merit dominated as the criteria for this. Free text comments reflecting this theme are included in Box 20. Further to these were comments pertaining to the ‘pipeline’, that female numbers alone would naturally correct the leadership gender gap (Box 21). Within the free text responses were a small number of statements (6) reflecting awareness that barriers might limit women seeking/achieving leadership. These are included in Box 22.

| Box 20 |

|---|

| “I always believe best person for the job”(M, 40+, Australia) |

| “get best person for position regardless of gender” (M, 70+, Australia) |

| “merit should be the only consideration” (M, 50+, Australia) |

| “should be based on ‘qualifications’ for those roles” (M, 60+, Australia) |

| “the most capable people ought be representing us, regardless of gender” (M, 50+, New Zealand) |

| “skill is more relevant than gender”(M, 70+, Australia), |

| “selection/election should be based on merits and leadership ability”(M, 60+, Australia) |

| Box 21 |

|---|

| “The historical anomaly of very few women in our profession has now been corrected (overcorrected substantially). It stands to reason that by sheer weight the numbers women will dominate all college positions in the future” (M, 50+, Australia) |

| “gender ratios in RANZCOG leadership groups will reverse in coming years due to significant feminisation of workforce” (M, 50+, Australia) |

| “I think weight of female trainees/fellows will address the imbalance in the near term” (M, 50+, Australia). |

| Box 22 |

|---|

| “I think we need to work harder to engage more of the Fellowship, make it easier for women to attend and encourage them to nominate” (M, 60+, Australia) |

| “There are better ways of increasing the number of women in leadership roles. Like this questionaries’ should do, identifying barriers and addressing them is a better strategy” (M, 50+, Australia) |

| “70% female recruitment to training programs should see greater than or equal to 50% representation on state councils within a decade. If not, the fellowship should ask why?” (M, 60+, Australia). |

Female specialist responders

Among the female specialist responders, 31% provided free text comments on gender quota use. Just over half of this cohort (56%) expressed an opposition to quota use at RANZCOG. The variation in opposition rates to gender quotas between male and female specialists were consistent with difference seen between genders seen in Table 9.

Within the responses opposing gender quotas use, the statement ‘best person for the job’ again resonated as the dominant theme. Within this ‘best person for the job’ theme, ‘merit’ (66%) and ‘the pipeline’ (12%) again represented the subthemes. Free text comments reflecting ‘merit’ are included in Box 23, and ‘pipeline’ in Box 24. The ‘merit’ subtheme reverberated strongly among both male and female specialists. Within this female specialist cohort, 50% of responders provided actionable changes that could reduce barriers to women seeking leadership including; “what needs to happen is that the practicalities i.e. meetings by tele conference, decentralisation, move exams out of central Melbourne - this will allow much wider participation” (F, 50+, Australia).

| Box 23 |

|---|

| “the most qualified or suitable person should get the position, irrespective of gender, race or colour” (F, 40+, Australia) |

| “appointments should be based on interest, motivation, passion” (F, 60+, Australia) |

| “The best candidates should hold positions regardless of gender” (F, 30+, Australia) |

| “I think people need to get there on merit. I think we have to ensure the blokes have got there on merit too (not just because of mates)” (F, 40+, New Zealand) |

| “please choose the best qualified and skilled applicants for the councils, I am against gender quota” (F, 40+, Australia) |

| “quotas are to be despised. They work against everything that feminism has fought so hard for. Positions should be on merit, not tokenism” (F, 50+, Australia) |

| Box 24 |

|---|

| “as our college graduates more women I am sure this will change with time” (F, 50+, Australia) |

| “most trainees are now female and the quantity will rise“ (F, 50+, Australia). |

Within the group of female specialist responders agreeing with ‘gender quotas’ use, 25% indicated a desire to have matched membership and leadership gender representation. Comments reflecting this subtheme of ‘authentic gender representation’ are included in Box 25. Another 23% of responders’ responses suggested quotas provide a tool to ‘highlight gender bias’, ‘change the culture’ and ‘reduce the gender leadership gap’ and, at a faster rate than the ‘pipeline’ (Box 26).

| Box 25 |

|---|

| “It is worth consideration as the councils gender mix does not reflect that of the general college” (F, 30+, Australia) |

| “look at college membership and then make it gender representative” (F, 50+, Australia) |

| “should reflect the makeup of trainees ie we have a predominantly female workforce now but leaderships roles are still heavily dominated by males” (F, 40+, Australia) |

| “gender ratios should be proportional to fellow/ trainee gender ratios” (F, 40+, Australia) |

| Box 26 |

|---|

| “Gender quotas help to ensure that all voices are heard despite the continuing bias against women” (F, 30+, Australia) |

| “Need quotas otherwise the problem is not highlighted” (F, 50+, Australia) |

| “I think that gender quotas are only useful as a short term solution to intractable discrimination, |

| to break down barriers and develop role models” (F, 60+, Australia) |

| “voluntary system too slow, need affirmative action” (F, 40+, Australia) “trickle-down isn’t working for us, so let’s go with quotas” (F, 40+, Australia) |

| “there is good evidence, from corporate models, that gender quotas do redress the uneven balance of men in management roles” (F, 50+, Australia) |

Survey – Concluding thematic analysis

Participants were invited to submit concluding comments at the end of the survey following the statement; ‘thank you taking the time to complete this survey…if you would like to add any additional comments please do so below‘. From the 770 survey respondents, 63 (8%) choose to write free test comments. The dominant theme within this concluding section was ‘solutions to reducing structural barriers for leadership’. Comments reflecting this only came from female responders (Box 27), and added practical steps to the suggested solutions to gender leadership equality in the gender quota sub-section of the results.

| Box 27 |

|---|

| “a public campaign to increase female participation, consider stipends/reimbursements that cover travel and childcare, create female sponsor networks” (F, 40+, Australia) |

| “I would suggest that job-sharing for RANZCOG committee positions be considered, as we did originally for job-sharing in training positions. (F, 50+, Australia) |

| “create job sharing for RANZCOG committee positions” (F, 40+, Australia). |

A smaller cohort of responders (mostly males), from both Australia and New Zealand referred back to their concerns that the feminisation of our specialty will reduce future opportunities for males. This was nicely summarised in the following statement; “there were 21 applicants for the interview to join the program last week. One was male. “Huston, we have a problem!” (F, 50+, Australia).